Begin Again: reckoning with intolerance in Maine was Installed May 27, 2021 through December 31, 2021 at Maine Historical Society's gallery in Portland. This online component expands content with Maine Memory Network items and differs slightly from the physical installation.

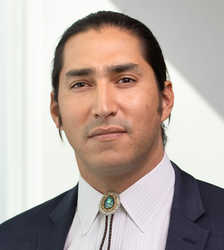

Curated by Anne B. Gass, Independent scholar and women's rights history activist; Tilly Laskey, curator at the Maine Historical Society; Darren J. Ranco PhD (Penobscot), Chair of Native American Programs, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Coordinator of Native American Research, University of Maine;

and Krystal Williams, Attorney and Executive Advisor, Providentia Group.

Advisors include: Ryan Adams, Matthew Jude Barker; John Banks (Penobscot); Mary L. Bonauto; Rhea Cote Robbins; Lelia DeAndrade; Angus Ferguson; David Freidenreich; Seth Goldstein; Michael-Corey F. Hinton (Passamaquoddy); Dr. Andrea Louie; Kristina Minister, PhD; Sherri Mitchell (Penobscot); Alivia Moore (Penobscot); Jennifer Neptune (Penobscot); Garrett Stewart; Charmagne Tripp; and Arisa White.

Begin Again is brought to you with generous support from: Jane's Trust, The Morton-Kelly Charitable Trust, Unum, Elsie A. Brown Fund, Inc., Maine Humanities Council, Margaret E. Burnham Charitable Trust, The Phineas W. Sprague Memorial Foundation, and the William Sloane Jelin Foundation.

Exhibition contents and navigation

Page 1 Introduction Page 2 Just Powers

Path A: Page 3 Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness--Path A Page 4 All men are created equal--Path A Page 5 We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor--Path A

Path B: Page 6 Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness--Path B Page 7 All men are created equal--Path B Page 8 We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor--Path B

Page 9 Maine Historical Society and reckoning with museums as colonial institutions

View the virtual exhibition through a 3-D online experience.

Terminology

Indigenous/Native/Native American/Indian--the first people of what is now known as the Americas.

Wabanaki—the first people of Maine encompassing the Abenaki, Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Nations.

Black—People of African descent and African Americans.

Colonialism—a policy of stealing political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.

Settler colonialism—a system that replaces the original population of the colonized territory with a new society of settlers through theft and force.

Triangular Trade/Atlantic Slave Trade—an economic system where merchants traded goods like rum and guns for enslaved people in Africa, who were sailed to the Americas as forced labor. The raw products of slave labor were traded for slaves and also shipped to New England for processing and sale.

White—descendants of European and English settler colonialists and those benefiting from Whiteness.

Begin Again: reckoning with intolerance in Maine

A pandemic, political unrest, race-based violence, and drastic economic inequities in 2020 have spurred conversations about intolerance in America and Maine. During this crisis, many are asking, How did we get here? The answer is centuries old.

A year after Christopher Columbus's 1492 journey, Pope Alexander VI issued a Papal Bull that legalized stealing Indigenous land in what is now known as the Americas, justifying the genocide of non-Christians. A previous proclamation in 1452 approved the murder and enslavement of African people. These "Doctrines of Christian Discovery and Domination" are the foundation of settler colonialist supremacy woven into all aspects of American life, and are a basis of the legal, economic, and social systems.

The Doctrines propelled English and European settlements through theft of Indigenous Homelands starting in the 1600s. The Doctrines shaped the ideologies of the Framers of the U.S. Constitution, who, while writing "all men are created equal," suppressed women's rights, lived on stolen land, and profited from slavery. These ideologies remain present, and were cited in the U.S. Supreme Court as recently as 2005 in City of Sherrill, New York v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York.

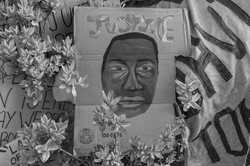

The roots of why, in 2020, a White Minneapolis policeman was empowered to kneel on the neck of George Floyd, a Black man, in full public view for 9 minutes 29 seconds are traced to the fundamental intolerance in our society based in the Doctrines of Discovery. The question shouldn't be, How did we get here?, but rather, Where do we go from here?

This exhibition examines different paths of experiences in Maine. There are difficult histories to reckon with, and some items might shock visitors. In collaboration with a network of advisors from around the state, we invite you to view Maine's history plainly, to work toward healing through truth, and "Begin Again," envisioning a more equitable experience that we know is possible for all of Maine's residents in the future.

Just Powers

The Doctrines of Christian Discovery and Domination

Indigenous people in what is now known as North and South America developed their own religions and governmental organization over millennia, but Europeans regarded their complex societies as "barbarous" and therefore open to colonize, convert, and enslave. Pope Alexander VI's Papal Bull Inter Caetera proclaimed all land not inhabited by Christians was open to be "discovered" by Christian Europeans—the basis of colonization.

Two Papal Bulls—1452 pertaining to Africa and 1493 to the Americas—are known as the Doctrines of Christian Discovery and Domination. These documents allowed European settler colonialists to profit through taking ownership of land and enslaving Black and Indigenous people. Although it is 528 years old, this Doctrine is the underpinning of American racism—and Christianity is at the center of it.

The Lasting Effects of the Doctrines of Discovery

My family is from the Cape Verde Islands, a small archipelago about 400 miles off the coast of Senegal.

The Cape Verde Islands were uninhabited until the 15th century when the Portuguese arrived. Sanctioned by the Doctrines of Discovery, they claimed the islands and used them in their quest to colonize Africa. They imported enslaved Africans, who were sold, or used to support the local economy. Like many other colonizers, the Portuguese also used their position of power and violence to create a new subordinate population of racially mixed people, and a racist hierarchy that rewarded all things White and Portuguese.

Over generations, as Portuguese interest and presence in the islands declined, the Cape Verdean population became truly multi-racial and the sharp racial divisions enforced by the Portuguese faded. It also developed its own unique culture—informed by, but different from, a myriad of Portuguese and African cultural practices and values. Cape Verdean resistance to Portuguese oppression also grew. Finally, in 1975 Cape Verdeans won their independence from Portugal.

This history leaves me in a complicated relationship with the Doctrines of Discovery. I see them as the impetus of violent exploitation, oppression and White supremacy enacted by the Portuguese. However, at the same time, I know that without it, my people, my culture, my history wouldn’t exist. No doubt this is a pattern common in history—from the bad, selfish awful, comes good, life, and strength.

—Lelia DeAndrade

Portland, Maine

America has never fully embodied equality, liberty, and justice. What it has always had was a dream of justice and equality before the law.

—Heather Cox Richardson, 2018

The Second Continental Congress representing 13 colonies in America declared their independence from Great Britain on July 4, 1776, and formed the United States of America. This founding document, one of 26 surviving copies printed by John Dunlap, is based on the noble principle that "All men are created equal," while in reality, it excluded women and people of color. Forty-one of the 56 signers owned slaves. William Whipple is widely known as the only Mainer to sign the Declaration of Independence—his merchant business participated in the Atlantic slave trade and he enslaved Africans on his Kittery estate—though during the American Revolution he freed some of his slaves and later supported emancipation.

The Declaration was a rallying cry to gather troops for the Revolution, and foreign support for the new government of the United States. When the Framers wrote the Constitution, the radical nature of equality celebrated in the Declaration was weakened in favor of protecting economic stability associated with property rights, therefore perpetuating inequality in society.

The line from the Declaration of Independence that always sticks out to me is the one that includes "we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal." That line is probably one of the most romanticized pieces of American prose ever written, yet it's just a poetic façade that masked the true beliefs of its slave-owning authors.

The majority of the signers literally owned human beings as personal property at the moment they signed beneath those audacious words. Were "all men" truly equal in the eyes of the Founding Fathers? Of course not. After all, just 21 years earlier, the Phips Proclamation of 1755 offered bounties for the capture and killing of Wabanaki people in what is now Southern Maine.

—Michael-Corey F. Hinton (Passamaquoddy)

The Maine State Constitution took effect on March 15, 1820 when Maine separated from Massachusetts. Maine's Constitution extended to:

Every male citizen of the United States of the age of twenty-one years and upwards, excepting paupers, persons under guardianship, and Indians not taxed.

The Constitution of the State of Maine and that of the United States, Portland, 1825

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

While the constitution provided strong protections for religious freedom, extended voting rights to Black men, and had no property requirement to vote, it disenfranchised women, the poor, and "Indians not taxed," recognizing Tribal sovereignty but also tying representation to taxation.

The Maine Constitution prohibits altering the Articles of Separation without the consent of Massachusetts. For this reason, and to avoid changing the Maine Constitution, Maine legislators instead suggested redacting sections of the document. Since 1876, Sections 1, 2, and 5 of Article X of the Maine Constitution ceased to be printed, but retain their legal validity. The redacted sections include Maine's obligation to uphold and defend treaties made between Massachusetts and the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot Nations.

The Maine Constitution and Hope for our Future

When I look at the sweeping and inspiring declaration of rights in Maine's 1820 Constitution, I see that they do not include me, a Black woman. While the entire document is worth a coffee-cup read, I focus on Article I, §§ 1-4 which, in certain respects, parallel the United States’ Declaration of Independence.

Sections 1 and 3 recognize the "natural" and "unalienable" rights of "all men" to enjoy and defend life and worship God. Those who opine that the use of the word "men" in the Constitution refers to mankind in general ignore the literary reality of the document and the historical context in which it was drafted. Despite being established as a free state, slavery had been practiced in Maine and women—White women—had limited legal rights; Indigenous and Black women had fewer still.

I am most struck by Section 2 which recognizes that "all power is inherent in the people; all free governments are founded in their authority and instituted for their benefit." History makes plain that "the people'" who were the intended and actual beneficiaries of the free governments were wealthy White men who benefitted—and continue to benefit—from governmental norms, enacted legislation, and the court decisions that uphold an unjust system.

Yet, it is also in Section 2 that I find hope for our future. When we Mainers unite and begin to recognize and affirm each other’s humanity, Section 2 also affirms that we have the, unalienable and indefeasible right to institute government, and to alter, reform, or totally change the same, when [our] safety and happiness require it. Our power to shape the systems that govern our society is our path to a future that works for all Mainers.

—Krystal Williams

The Doctrine of Discovery and the US Supreme Court

Johnson v. M'Intosh is a Supreme Court case in which two White men sought to determine who, between the two of them, had the right to claim ownership over a parcel of land that was Piankeshaw Nation Homelands. Johnson's forefathers 'purchased' the land directly from the Piankeshaw. M'intosh claimed he received the land under a grant from the United States. The Court relied heavily on the 1493 Doctrine of Discovery when determining that M'intosh was the rightful owner of the land. It was at this point in 1823 that the Doctrine of Discovery was officially incorporated into U.S. common law.

According to the Court, the Piankeshaw Nation did not have the legal right to sell land to Johnson, an individual, because, discovery gave [england, as the discoverer] an exclusive right to extinguish the Indian title of occupancy, either by purchase or by conquest; and gave also [england] a right to such a degree of sovereignty, as the circumstances of the people would allow them to exercise. The sovereign right to the land "discovered" by England passed to the newly independent United States.

This case is a clear example of the court system upholding an oppressive, unjust power structure. The Court acknowledged "title by conquest is acquired and maintained by force. The conqueror prescribes its limits." These limits are, apparently, even beyond the power of the Court to moderate as evidenced by the Court's position that "conquest gives a title which the Courts of the conqueror cannot deny, whatever the private and speculative opinions of individuals may be."

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

Christopher Columbus to the Pejepscot Proprietors

Click here to see maps and manuscripts

View the slideshow detailing how what is now Maine transferred from Wabanaki sovereign land to European ownership.

The place now known as Maine is—and always has been—Wabanaki Homelands. Colonization of this place was accomplished through various forms of theft and violence based on the Doctrines of Discovery and at great cost to Wabanaki people. When English people arrived in what is now known as Maine, Wabanaki leaders worked to incorporate the settlers into their social and ecological networks, to create responsible relationships, and alliances with their guests—efforts that were misinterpreted by the English as "ownership" of land.

Maine was part of Christopher Columbus's claim for Portugal and Spain. Over the next 500 years, other countries claimed parts of Maine, but it wasn't until the early 1600s that Ferdinando Gorges and John Popham, who spent years unsuccessfully colonizing Ireland, focused on Maine in the name of England.

Motivated by the prospect of economic gain from furs and timber, Gorges received a charter from King James I of England, and for more than 40 years he directed the colony's development as the self-proclaimed "Lord of the Province of Maine." Massachusetts annexed the District of Maine in 1652 after Gorges's death. Land speculation and patent companies like the Kennebec and Pejepscot Proprietors capitalized on these legacy land holdings and emphasized their connection to previous generations like Gorges to legitimize their claims. Competition and overlapping land claims were a common occurrence.

Thomas Purchase, an agent of Gorges in what is now Brunswick, Maine, ran a trading post and made real estate transactions. In the 18th century, the Pejepscot Proprietors legitimized some of their holdings by tracing the land ownership from Richard Wharton through Thomas Purchase to Gorges and attempted to reaffirm ownership through signed Indian deeds and documentation.

Massachusetts's policies and unequal relationships with Wampanoag people led to King Philip's War and the successive Colonial Wars for nearly 100 years, which greatly affected the lives of Wabanaki people and settler colonialists in Maine. During this time, land patent businesses like the Pejepscot Proprietors carved up Wabanaki territory and trading posts regularly cheated Indigenous people, adding to strained relationships.

Ulster Scots arrive in Brunswick

British leaders promoted Scottish migration to Northern Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries. Known as the Ulster Scots or Scots Irish, they attempted to colonize on "plantations" and promoted the Presbyterian faith. Facing discrimination and violence in Ireland, the Ulster Scots negotiated across the Atlantic with Massachusetts Governor Shute to settle the frontier of what is now Maine, and to "hold back" the Native people, who had most recently wiped out English settlements along Maine's coast during King Philip's War. Ironically, the Ulster Scots came to Maine seeking religious and economic freedom for themselves, but felt no remorse at taking these rights away from Wabanakis.

Presbyterian Reverend James Woodside brought one of the first boats from Bann County, Ireland with 40 families to settle in the Merrymeeting Bay and Maquoit Bay areas of Brunswick in 1718. Woodside was the second pastor hired by the Pejepscot Proprietors to minister to locals and the Wabanaki, but the town quickly determined Woodside wasn't puritanical enough to continue preaching. James Woodside returned to England in 1720, but his son William stayed in Brunswick, running a trading post and working at Fort George.

The Woodside family lived four miles from Brunswick's town center on Maquoit Bay. There they built a garrison house that was a space for trading with Wabanaki people, and acted as a safe house for the community during the Colonial Wars. In 1727, William was convicted of cheating Wabanaki people at the trading post. Over time, William gained enough money—likely in part from overcharging Wabanakis and other customers— to purchase 350 acres of land from Bunganuc Creek to Wharton Point in Brunswick.

The Ulster Scots families who came to Maine with James Woodside planned to stay together as a community. In Brunswick the descendants of the first Scots Irish—including the Woodsides, Dunnings, Dunlaps, Givens, Simpsons, Wilsons, and McFaddens—have remained in the area. Census data confirms that per capita, Maine has the highest percentage of self-identified Scots descendants in the entire United States, and ranks third in the country for Ulster Scots descendants.

Attacks in Brunswick, 1756

Wabanaki people tried to control illegal settlements and pushed back against encroachments into the interior, specifically after declaring that British forts were unwelcome during peace negotiations.

As a result, the homes of Ulster Scots were attacked by two parties of Wabanaki men in the Pejepscot Patent area. Thomas Means settled on Flying Point Road in Freeport. He and his infant son were killed and Molly Phinney was taken captive by one party. The other party went to Maquoit in West Brunswick and traveled across Middle Bay to the home of John Given, but "Seeing no one but children passed them unmolested." Later they encountered Abijah Young and John and Richard Starbird, and took Young prisoner.

Why was Brunswick targeted in 1756? A likely contributing factor was the increased bounties Massachusetts put on Native people—specifically on their scalps. Reverend Thomas Smith in Falmouth Neck (Portland), about 25 miles south of Brunswick noted in 1745 "People seem wonderfully spirited to go out after the Indians."

By June 1755, Massachusetts declared war against all "Eastern Indians," except the Penobscots. When the Penobscot diplomacy failed and they refused to fight alongside settlers, Massachusetts governor Phips issued a proclamation in November expanding the war to include the Penobscot Nation. By 1756, scalp bounty payouts for men, women and children approached 300 English pounds per person, equal to about $60,000 today.

Wabanaki people were being hunted in their Homelands and retaliated.

Reverend Thomas Smith and scalp bounties

In 1755, when Maine was part of Massachusetts, an official Proclamation by Lieutenant Governor Phips of Massachusetts offered:

● 50 pounds for every male Penobscot Indian above the age of twelve years old taken alive (live captives would likely be sold into slavery in the Caribbean or to other distant buyers);

● 40 pounds for every scalp of a male Penobscot Indian above the age of twelve years old;

● 25 pounds for every female Penobscot Indian taken and brought in and for every male prisoner under the age of twelve years old;

● 20 pounds for every scalp of such female Indian or male Indian under twelve years of age.

Reverend Thomas Smith of First Parish Portland

Click here to read an expanded story by Kristina Minister.

At Falmouth Neck (Portland), the Reverend Thomas Smith, pastor of First Parish Church, responded to the call for sanctioned violence against the Wabanaki. In 1757, Smith and prominent members of the church equipped a posse of 16 men. These "scouters and cruisers" were sent to "kill and captivate the Indian Enemy" to the east of Falmouth in the area between the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers. Shortly after, Reverend Smith noted in his journal the receipt of 198 British pounds for "my part of the scalp money"— equal to one-quarter of his salary.

Smith and other English colonists who founded First Parish Church not only organized genocide of the Native people, they strove to grow personal fortunes by populating Maine with White settlers. The 1755 Proclamation offering bounties to hunt and kill Penobscots was but one of dozens of such programs in the Massachusetts Colony's campaign of "ethnic cleansing" targeting the Wabanaki all across the Northeast region during Reverend Smith's lifetime.

The real history of how Maine came to be 95% owned and populated by people who identify as White is encapsulated in the obscured, early history of First Parish, and the profitable investment by a few wealthy church members and their pastor in the government-sanctioned, systematic dispossession, and genocide of Wabanaki people.

—Kristina Minister, Ph.D.

Member, First Parish Church, Portland

All Men are Created Equal

William Pepperrell, merchant and slave owner

William Pepperrell (1696-1759) of Kittery was an English merchant, officer, and Governor of Massachusetts—which Maine was part of until 1820. Along with other settler colonialists, his wealth was derived from the labor of Black and poor people, and based upon the theft of Native lands. Pepperrell owned, bought, and sold African enslaved people throughout his life.

Slavery of African people existed in Maine within English-speaking settlements, and while often considered an institution of the American South, the profits from enslaving people—both Indigenous and Black—helped build many of Maine's businesses, industries, and coastal communities. Even families less prominent than the Pepperrells forced slaves to do their hard labor. New England slave owners were more likely to own one or two slaves, rather than hundreds.

When a shipment of rum and enslaved people consigned to William Pepperrell arrived in Kittery on the ship Sarah from Barbados in 1719, Pepperrell wrote the ship's captain, Benjamin Bullard,

I received yours by Captain Morris, with bills of lading for five negroes, and one hogshead of rum. One negro woman, marked Y on the left breast, died in about three weeks after her arrival, in spite of medical aid which I procured. All the rest died at sea. I am sorry for your loss. It may have resulted in deficient clothing so early in the spring.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts outlawed the slave trade in 1787 in both Massachusetts and the District of Maine, but an illegal trade continued.

Maine and the Atlantic World Slave Economy

The average lifespan of an enslaved African, once they arrived in Cuba, was seven years. These individuals were literally worked to death. In the 1800s, Cuba produced much of the world’s sugar. This matters to Maine history because Cuba was Portland’s primary trade partner in the early to mid-19th century. The profits from such trade were so lucrative that Cuba’s forests were cut down and the fields grew sugar cane almost exclusively.

Maine provided the lumber that built the plantations, as well as food that fed the enslaved Africans. One 20th century maritime historian described how whole houses, broken down, were shipped to Cuba along with parsnips, beets, potatoes, salt cod, board lumber, and oxen to work the sugar presses. Maine also shipped broken-down wooden boxes and casks to be assembled once they reached Cuba. Coopers from Portland traveled to Cuba to assemble these containers and filled them with sugar, molasses, and rum.

Pearlware sugar bowl, Portland, ca. 1830

Sugar bowls are a reminder of the legacy of colonization and slavery attached to Maine businesses and industries.

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

Sugar cane products like molasses, in turn, were shipped to Maine where the tallest building on the Portland waterfront was the J.B. Brown sugar refinery, the Portland Sugar Company. The refined sugar graced dining tables throughout the region and this luxury product was exhibited in ornate sugar bowls.

In 1860 Portland was processing 20 percent of all the molasses that was imported into the U.S., more than any other city in the country. Some of the molasses supplied one of the seven rum distilleries that dotted the Portland waterfront. Some of this rum was then shipped to West Africa, where it was used to purchase and enslave Africans.

Many of the ships involved in transporting enslaved Africans across the Atlantic were built in Maine, and captained and crewed by Mainers. This is true both before and after the slave trade was declared a "piratical" act in 1820, punishable by death. It is notable that the only individual ever disciplined to the letter of the law was Captain Nathaniel Gordon who hailed from Portland. He was hung in 1862 after being convicted for carrying 897 enslaved people aboard the merchant ship Erie. Half of the enslaved people on the ship were children.

—Seth Goldstein, Academic Faculty, Maine College of Art (MECA)

Letter to Elizabeth Mounfort from a friend in Trinidad, Cuba, July 4, 1847

"I should like to spend some time in the country, were it not for the shrieks of the slaves, which you hear constantly, some one or another, being nearly all the time at the whipping post."

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

John Bundy Brown and Maine's sugar industry

John Bundy Brown (1804-1881) was one of Maine's wealthiest businessmen, his fortunes based in the sugar industry and real estate. Brown began his career in the wholesale grocery business and branched into sugar and molasses with the Portland Sugar Company, a successful venture from 1845 to 1866.

Sugar—called "white gold" because of its huge profit margins— is linked to colonization and slavery. Christopher Columbus brought sugar canes to the Americas in 1493. Deploying the Doctrines of Christian Discovery and Domination of 1452 and 1493 to support their actions, Europeans stole Indigenous lands in the Caribbean to grow the sugar cane, and forced enslaved Africans and Indigenous people to tend and harvest sugar crops, which were flourishing by 1515. Sugar was a leading commodity in the Atlantic slave trade.

By 1860, the Portland Sugar Company helped position Portland as the top American city in the sugar refining market. In 1865, the factory was using 30,000 "hogsheads" (barrels) of molasses a year, processed into 250 barrels of sugar a day. Portland's Great Fire of 1866 destroyed Bundy's refining warehouse, but the resources from this successful business helped support his future ventures, and even rebuild the city after the fire's devastation. Other businesses like Forest City Sugar Refining and the Eagle Sugar Refinery continued operations in Portland until 1891, but once slavery was abolished in Cuba in 1886, the businesses ceased to be profitable.

As of 2021, sugarcane continues to be a crop associated with inequity and is consistently in the top five products—along with gold, bricks, tobacco, and coffee—that are produced using child and forced labor.

Timber and Shipping, Triangular Trade, and Maine Businesses

Maine timber and shipping industries benefited from slavery through what is known as the "triangular trade" or the Atlantic slave trade. Maine-built ships, captained and crewed by Maine men, carried iron, cloth, brandy, firearms, and gunpowder to Africa. On the return journey, the ships brought captives for sale to American slaveholders.

Congress outlawed the slave trade in 1808, although it continued illicitly for years afterward. Yet with no prohibition against transporting slaves within the United States, or of products made by them, many business opportunities remained. With our extensive forest, navigable rivers, and coastal port cities, by the mid-19th century, Maine was the largest producer of ships in America. Maine ships brought lime, ice, lumber and food to the Caribbean, where slaves produced sugar cane in brutal conditions. The ships brought back sugar for processing and partially refined molasses for sale to Maine distilleries, where it was turned into rum.

Similarly, Maine had a brisk trade with the American South, bringing cargo such as canned fish or corn, ice, lime, granite, and textiles for sale there, and returning with raw cotton produced by southern slaves for use in the textile industry here, and guano for use in fertilizer. Maine even imported lumber from the South to meet the insatiable demand generated by the shipping and building industries, along with recruiting recently arrived European and Franco immigrants to work in the lumber camps.

We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor

The Ku Klux Klan in Maine

The Klan in Maine rose rapidly because a charismatic leader was able to rally middle-class Protestants around their opposition to immigrants and Catholics.

—Rainey Bench, 2019

Because Maine is predominately White, it might seem out of context that our northern state hosted the largest Ku Klux Klan chapter outside of the South during the 1920s. The "new" Klan formed in 1915—a time of heightened patriotism, nativism, and anxiety about the future—based on discrimination and violence to Black people and people of color, but further targeting Roman Catholics, Jews, and recent immigrants.

"Nativism" protects the interests of "native-born" or established people of a place against newcomers or recent immigrants. Since Wabanaki people have lived in what is now known as Maine for at least 13,000 years, the philosophy of nativism in Maine's KKK movement is absurd, but dangerous. Oral histories recount Klan intimidation of Wabanaki people, including the burning of crosses in Milford, just across the river Indian Island and the Penobscot Nation.

Maine's leadership in the anti-slavery movement and large volunteer participation in the Civil War furthered the emancipation of Black enslaved people, but in the context of systemic White supremacy and intolerance, Maine has had centuries of experience with racially motivated discrimination.

The Ku Klux Klan in Maine grew in the 1920s under the charismatic leadership of F. Eugene Farnsworth. Born in Columbia Falls, he toured the state appealing for better government and stronger adherence to patriotism, Protestant values, and the Bible. By 1923, the Klan reportedly had statewide membership of 150,000, or 23 percent of Maine's population.

The Klan became less visible by 1930 with a rapid decline in membership, the emergence of the Great Depression, and several scandals involving bribery, adultery, embezzlement, and bootlegging. The robes of members might have been packed away, but the Klan never really left Maine; in 2017 the Ku Klux Klan left neighborhood watch recruiting flyers in Freeport and Augusta.

From Away in terms of Wabanaki Homeland

kči-čči (The Great Penetrating Arrow), by James Eric Francis Sr., 2019

Item Contributed by

Hudson Museum, Univ. of Maine

Maine is an interesting place. Anyone who has spent time here knows that identifying as a Mainer is not as simple as moving here and establishing residency. "Real Mainers" often trace their presence in the state across the number of generations their families have been here, differentiating their claim to our placed-based identity from those "from away," who are viewed as not quite fully established.

The generational heritage has also been tied to forms of work in Maine's forest or along the coast. While these notions of working the land and becoming part of it, and it a part of you, is a common theme across cultures and societies, the applications of this in Maine have also always been ethnocentric and racialized.

Part of the Doctrines of Discovery as they were applied by the English in North America recognized only the working of the land by Englishmen "improving it" as the way to truly establish a property right. Wabanaki and other Indigenous land practices were specifically excluded from establishing a property right. Similarly, the "real Mainer" category has always implicitly excluded Wabanaki people from this category, wherein thousands of years of presence on the land somehow never fit into the quaint category of a "real Mainer" claimed by so many, whose families stretched back only a few generations, not the hundreds of generations of Wabanaki presence in what is now Maine.

—Darren Ranco

Playing Indian

In 1998, Philip J. Deloria published the book Playing Indian, revealing the many ways in which White American identities are tied to romanticized notions of Native Americans. "Playing Indian" is a part of the American mythology, allowing for both the performance of being an Indian by non-Indians, while at the same time erasing the presence of actual Indians and their actual cultures.

Deemed as "fun" and a "normal" part of American childhood, these appropriations and misrepresentations of Native people have been proven to cause psychological harm to Native children, leading the American Psychological Association to ask for the end of American Indian mascots in 2005.

Moreover, these appropriations and erasures of actual Indians have also meant that the general public largely ignores or lacks knowledge of the rights and experiences of Native Americans, who have almost no presence in American popular media.

Blackface

There is no more sacred honor than to see someone—to truly see them and affirm their personhood. It is the free gift that we give each other with each smile, with each meeting of the other's gaze.

The use of blackface is offensive for many reasons, the roots of which strike at the simultaneous denial and mocking of Black personhood. At this time in Maine's history—the early 20th century—Black peoples were free from the shadows but not the stain of slavery and second-class citizenship. In short, Black people would not have been present at this gathering as social equals.

Blackface is also often accompanied by caricatures of Black cultural norms and learned behavior. Undoubtedly, the audience at this play likely composed of family and neighbors, reacted favorably to what they probably considered a humorous depiction of the Black lives that they mainly saw through a social veil of "lesser than."

—Krystal Williams

Where are the French?

Lewiston is a typical example of le petit Canada, as are many others located throughout the state of Maine where the French settled. All classes of French people immigrated between 1820 and 1920—the elite, the professional class, and the workers destined for the mills.

Living in Little Canada meant a city-within-a-city. Survivance—Notre foi, notre langue, nos institutions (our faith, our language, our institutions) was the credo of surviving and holding onto their identity.

Le Messager, the French language newspaper in Lewiston from 1880 to 1966, kept the community connected. Camille Lessard Bissonnette was a correspondent for the newspaper, and a suffragist. Bissonette wrote about the complexities of the already arrived and the newly arriving immigrant in her book, Canuck.

The prejudices toward the French were expressed through English-only, Maine state legislation in 1916 and 1919 prohibiting French as a language of instruction in schools other than in high school language classrooms. But then, the National Defense Education Act, signed into law by President Eisenhower in 1959 due to Sputnik, stated language learning was a top priority to national security. The KKK also espoused prejudices toward the French; by 1925, Maine's KKK membership was recorded as 150,141.

Despite all of the challenges, the French heritage population is deeply woven into the fabric of many Maine communities.

—Rhea Côté Robbins

Executive Director, Franco-American Women's Institute

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

Maine is Wabanaki Homelands

Wabanaki people, including the Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Abenaki Nations, have inhabited what is now northern New England, the Canadian Maritimes, and Quebec, since time immemorial according to oral histories, and for at least 13,000 years according to the archaeological record.

The Wabanaki Confederacy, hundreds of years old, is defined not only by a set of diplomatic protocols and persuasive discourse, it seeks out international relationships to address interconnected problems across the greater Wabanaki territory.

Critical to its functioning is the shared knowledge between the Wabanaki Nations that our landscapes are alive with our relations and collective responsibilities to serve one another, human and non-human, ancestors and future generations, for a greater good.

Fundamental to protecting Wabanaki cultural and natural resources is the understanding that if we take care of the resource, it will take care of us—for example, healthy ecosystems of sweet grass require the picking of it each year by Wabanaki artisans and gatherers.

—Darren Ranco

A blanket coat for Margaret Moxa by Jennifer Neptune

I made this blanket coat in memory of a Penobscot family, Margaret Moxa, her husband, her two-month-old baby; and a separate group of eight Penobscot men and one child, who were all murdered by a group of scalp-bounty hunters the evening of July 2, 1755 in what became known as the Owl's Head Massacre. The accounts of that evening are horrific, Margaret begged for her baby to be spared and brought to Captain Bradbury at the Fort, instead she was forced to watch her child's murder.

Margaret had become a friend to the English women who resided in Thomaston at Saint George's Fort, making regular visits to them. The grief of the women at the fort upon learning the fate of their friend Margaret Moxa was reported in accounts to be "deep and unappeasable." The group of Penobscot men and the child traveling with them were returning from a peace conference at the fort.

James Cargill, of Newcastle, purposely led his expedition into Penobscot territory, even though the Penobscot were exempted at that time from the bounty proclamation issued in June of 1755 that targeted the Abenaki of the Kennebec region.

When Cargill and his group reported to the Fort the following day with the scalps, they were refused supplies and were reported to the authorities in Boston on massacre charges. Cargill was arrested and jailed.

In November of 1755, Lt. Governor Phipps of Massachusetts declared war and issued a scalp bounty proclamation on the Penobscot for refusing to agree to move to English forts for surveillance as the English feared Penobscot retaliation. Instead, Penobscot people living in the area moved to territories further inland for safety. Cargill was released to fight in this war, and in 1757 he was acquitted of the massacre charges by a jury in York, Maine.

In 1758 Cargill, who had kept the scalps of the 12 murdered Penobscot people, attempted to turn them in for payment. Massachusetts government debated, and ruled to deny him payment. The report stated, "And it passed in the negative, in as much as it does not appear that the said Indians were such with whom this Government was then at War."

—Jennifer Sapiel Neptune (Penobscot)

A poem for Margaret Moxa

When I heard her story

I cried myself to sleep for weeks

I couldn't stop hearing her baby crying

and her anguished wails as she pleaded for life

from 31 men who had forgotten how to be human,

with hearts that hate had turned to stone.

Blanket Coat by Jennifer Sapiel Neptune, Indian Island, 2021

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

We have stories about those who have lost their souls

Windigo, Chenoo, kíwahkʷe,

hearts of ice, with greed and hunger

that can never be satisfied,

cannibal giants, who prey on horror.

I think of the old Passamaquoddy story of the woman who was able to

turn a Chenoo back to human with her kindness, by treating him as a relative.

I wonder if Margaret thought of that story too

as she looked into their eyes for mercy and found none.

This blanket is my prayer of transformation,

Like my ancestors have done for the past 500 years

I will take the treaty cloth, the cloth of broken promises;

the silken ribbons of deception,

the glass beads of ill intent,

and like Margaret Moxa,

and those that reached out their hands before me,

I will attempt to stitch a prayer so powerful

that it creates a blanket that melts through ice veins,

and through generations with forgiveness,

so that those that hate find their hearts,

and all men turned Chenoo rejoin the human race.

May I have stitched a prayer so full of love, tenderness, and beauty

that it reaches back 266 years

and wraps the innocent in the love of the survivors;

and with such gentleness,

that it comforts the baby's cries.

Jennifer Sapiel Neptune, 2021

Penobscot Nation

A Treaty of Alliance and Friendship

As the Declaration of Independence was being signed, the brand-new United States of America and the Wabanaki Nations, including the Maliseet, the Mi'kmaq, and the Passamaquoddy, were preparing to execute America's first diplomatic success: a Treaty of Alliance and Friendship (now known as the "Watertown Treaty") which was executed just days after the Declaration of Independence and had two primary goals.

First, the Continental Army was on the losing end of a war with the better supplied and trained British Army and needed help, badly. The Treaty of Watertown ensured that Wabanaki warriors would immediately travel to New York to bolster General Washington's force, and secured a pledge of assistance from the Wabanaki to defend what would become the Northern border of the United States.

Second, the Treaty was intended as a statement to the European Nation-States to announce that the United States was prepared to establish diplomatic and military alliances to protect its territorial and sovereign integrity.

At its core, the treaty was a promise of peace and friendship. The Americans received the better end of that bargain. The Wabanaki helped the rebels vanquish the Crown from America only to see the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and State of Maine install themselves as colonial overlords to whom Wabanaki lands and resources were nothing but opportunities to create material wealth. The bountiful natural and marine resources that once sustained the Wabanaki People became the capital investments needed to create "new" wealth in non-Native lumber towns and fishing communities throughout the state.

Following the American Revolution, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and later the State of Maine entered into new treaties with the Wabanaki Nations that included pledges to protect lands and resources reserved by the Nations. These pledges of peace, friendship, and protection were explicitly incorporated into the Maine Constitution, but the State of Maine has ignored and undermined those obligations since 1820. Whether through the theft of the Penobscot Nation's treaty reserved townships or the flooding of Indian Township to power lumber mills, the Wabanaki Treaty rights referenced in Maine's Constitution have never been properly respected.

—Michael-Corey F. Hinton (Passamaquoddy)

Thomas Jefferson contemplating the sale of Indigenous Homelands, 1776

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) was a delegate from Virginia to the Continental Congress during the American Revolution, the primary writer of the Declaration of Independence, the third President of the United States, and a slave owner.

Thomas Jefferson contemplating the sale of frontier land, Philadelphia, 1776

Item Contributed by

Maine Historical Society

In this letter, Jefferson contemplated selling or giving "unsettled land" to the west—otherwise known as Indigenous Homelands—to poor immigrants following America's divorce from Great Britain.

Jefferson's opinion that the western territories were open for the taking without considering Indigenous sovereignty demonstrates the settler colonialist viewpoints that began with the Doctrines of Discovery, and became cemented into the U.S. governmental structure. Jefferson's zeal for the Revolution and distaste for Indigenous Nations is evident on the last page of this letter, where he mentions the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Six Nations), the Senecas, the Shawnee (Shawanese), Delawares, and foreshadows the Cherokee Trail of Tears,

We directed a declaration to be made to the Six Nations in general that if they did not take the most decisive measures for the preservation of neutrality we would never cease waging war with them while one was to be found on the face of the earth. They immediately changed their conduct & I doubt not have given corresponding information to the Shawanese & the Delawares. I hope the Cherokees will now be driven beyond the Mississippi & that this in future will be declared to the Indians the invariable consequence of their beginning a war. Our contest with Britain is too serious & too great to permit any possibility of avocation from the Indians. This then is the reason for driving them off, & our Southern colonies are happily rid of every other enemy & may exert their whole force in that quarter.

The letter's recipient, Edmund Pendleton (1721-1803) was the Speaker of the Virginia legislature and a slave owner. Pendleton proposed the modification in the statement of universal rights in Virginia's declaration to exclude slaves, thus winning support of slave owners.

#Landback–A New Beginning for Wabanaki Land Relationships

The Wabanaki Tribes of what is now Maine sustained themselves for thousands of years living a community lifestyle based on the availability of land and natural resources. They moved with the seasons, adapting to Mother Earth's natural cycles. They practiced land and natural resource conservation as an integral part of daily living. They understood the need to let enough fish pass upstream of harvest sites so the migrations would continue to feed the people in future years. They conducted wildlife habitat improvements by prescribed burning in order to increase the availability of browse for big game animals. Individual family groups had their hunting territories based on watershed boundaries, and hunting pressure was managed through the geographical movements which allowed areas to recover after being harvested.

When the settler colonialists arrived they found vast old growth forests with abundant natural resources. Compared to the forests in Europe the area was often described as "park like" with its beauty and tall pine trees. This period of contact led to the exploitation and eventual industrialization of the forest, which changed forever the harmonious relationship the Wabanaki Tribes had enjoyed for millennia. Under duress, treaties were entered into with states and most of the Indigenous land holdings were lost. Because of their intimate knowledge of the geography and the forest ecosystem, many tribal men were able to find work as hunting and trapping guides, or work on the log drives on the waterways.

In recent years, the Wabanaki Tribes have once again been able practice some of their cultural traditions on tribal lands due to the return of stewardship responsibilities on lands acquired as a result of the Maine Indian Land Claims Act of 1980. In 2021, tribes are asserting themselves as the original stewards of their traditional Homelands, working with non-tribal landowners and land trusts to develop mutually beneficial relationships that redefine how land conservation is viewed by the larger dominant society. Concepts of land stewardship responsibility are replacing models of land ownership and control that have been the norm for centuries.

As people become more aware of the needs of society to have natural places remain on the landscape, and that return of land stewardship responsibilities to Maine's original people is not a bad idea, our Wabanaki tribal people remain hopeful for a future that includes being able to continue practicing traditional customs that define them.

—John Banks (Penobscot)

Director of the Department of Natural Resources for the Penobscot Indian Nation

Waponahki Women's Leadership

One of the most destructive impacts of colonization for Waponahki (Wabanaki) Nations has been the disruption of our traditional matrifocal and matricultural ways of being, not only in relation to our governance systems but in the overall sociocultural structure of our families, clans, and nations.

Traditionally, the women were centered in our societies. The clan mothers were the primary decision makers on all issues impacting our nations, including decisions related to land and other sources of survival for our Peoples. The women were honored as the givers of life and were trusted to provide balanced guidance for protecting, nurturing, and cultivating the lives of tribal members. The dehumanization of women that accompanied colonization violently removed our women from the center of our societies and sent our traditional systems into disarray. As a result, our people suffered. Therefore, we know the true value of our women and we recognize that they are crucial to our cultural survival as Waponahki Peoples.

Waponahki women are once again at the center of our communities. They are leading the work to recover our traditional ways of knowing and being, through language programs, renewal of kinship networks, and the revitalization of land-based teachings that focus on the relationships that exist between all systems within creation. The women are also decolonizing our stories, developing pathways for food sovereignty, and protecting of our lands and waters.

If we hope to continue our progress toward cultural revitalization and cultural survival, we have to ensure that our women are protected while they do the work of interweaving vital cultural knowledge into all aspects of community life, including all moves toward greater self-determination and sovereignty. Centering Waponahki women is the key to saving Waponahki Nations.

—Sherri L. Mitchell Weh’na Ha’mu Kkwasset (Penobscot)

Executive Director, Land Peace Foundation

Rematriation

How we treat the earth reflects how we treat each other. Our shared future for all people in Wabanakiyik calls us to rematriate. The Wabanaki nations exist and were developed in reflection of and humbling ourselves to this land for at least 12 millennia. To truly shift our values, we must acknowledge matriarchies as the human law of the land again.

The future of the land is, undoubtedly, its liberation. As a sovereign being, the earth will always take its course to restore balance, and there is an opportunity for us to collectively embrace this reality. We can choose to mirror the earth's propensity for balance and with that, we can allow for the possibility of human liberation. What we must do is respect the land. We must humble ourselves to understand that we can't heal it. We are not the earth's saviors. We may make claims to the earth by imposing our laws and our private and collective ownership structures on it, but ultimately the land cannot be owned. We are derived from the land, it holds us rather than any of us truly being land holders.

The objective of Maine and the United States as settler states is to completely replace the indigenous people, indigenous laws, values and relationships with those of the settlers'. However, white supremacist settler colonialism is not complete. Indigenous, Black and Brown relatives' resistance is the transformative leadership human society needs. Colonial relations to the earth and one another, i.e. capitalism and hierarchies, are not legitimate nor inevitable. Remember, the American project is in its infancy. Wabanaki Nations are the human elders of this land. Let our matriarchies lead for the betterment of all.

Rematriation efforts must also center two spirit and Indigenous queer folx to step into our power and lead. We are in a time of crisis, we need radical change—a change that brings us back to the roots of how we relate. Our indigenous queers and two spirits are living embodiments of sovereign, decolonized identities. Our existence is a connection to tradition. We are not supposed to be here in the patriarchal, white supremacist settler-colonial society. But here we are. We are living breathing alternative ways of being, seeing and of organizing our families, societies and politics. Two spirits can be, and I feel it is our responsibility to be, agents for a more just way forward. An elder shared that not only are two spirits welcome in Wabanaki communities but we are needed. Our gifts are needed for the health of our entire communities. We are examples of balance, flexibility and responsiveness; these are lessons for the underpinnings of climate adaption and for rebalancing our social, political and economic systems.

—Alivia Moore (Penobscot Nation)

Eastern Woodlands Rematriation and Wabanaki Two Spirit Alliance

All Men are Created Equal

Why is Maine so White?

Within a few days of moving to Portland in 2014, I first heard the phrase "from away." To me, a new Black Mainer, the use of the phrase seemed alienating and designed to reinforce the demographic profile that keeps Maine listed as one of the Whitest states in the Union.

When a Maine Public Radio listener posed the question, Why is Maine so White? in 2019 the initial response pointed to the lack of plantation farming inferring that Maine's reliance on "forestry, shipbuilding and textile and mill industries" made it immune to slavery.

Black people have been in Maine since the first settler colonialists arrived. Even though Maine was established as a free state under the Missouri Compromise in 1820, slavery was present since the 1600s in Maine and Mainers continued to benefit from slavery elsewhere in the U.S. and around the world after statehood.

Despite being home to prominent abolitionists such as General Oliver Howard or Samuel Fessenden, in general, White Mainers were not immune to the lure of slavery or to the narratives that dehumanized the enslaved. This response raises its own set of complexities and exposes Maine's dual identities that exist today.

Maine is where Macon Bolling Allen, the first Black attorney in the United States, was admitted into practice on July 3, 1844. Maine is also the place where the multi-racial community of Malaga Island residents was forcibly removed by the governor's edict in 1912.

Maine is the home of the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment which, despite impossible odds (and no ammunition), refused to retreat in the face of Confederate soldiers. Their courage and heroism played a decisive role in the Battle of Gettysburg and the Union victory in the Civil War. And, Maine is the place where, just a few miles outside of its major cities like Portland, Lewiston-Auburn, or Bangor the Confederate flag is prominently displayed.

Maine is a state with two conflicting identities—which Maine will win? The Maine that will be remembered by future generations is the Maine that we choose to nurture now.

—Krystal Williams

Restrictive covenants and race

From the Doctrines of Discovery to 2021, the systematic dispossession of land and exclusion from land ownership has been a primary way in which wealth has inured to White America. At the turn of the 20th century, ordinances across U.S. cities and towns used racially-explicit zoning laws to segregate the races.

When this practice was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1917, private developers created racially restrictive covenants. Such covenants were agreements entered into by groups of property owners or subdivision developers that kept them from selling their property to specified groups because of race, creed or color for a definite period unless all other property owners in that subdivision or community approved of the transaction. Restrictive covenants became the dominant mechanism to keep non-Whites (and, in many cases, Jewish Americans) out of communities throughout the 1920s through the 1940s. Restrictive covenants "ran with the land," meaning that the restriction became inherent to the property itself. Restrictive covenants were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1948.

The practice of redlining, in which lines were drawn on city maps to define ideal geographies for bank investments and mortgages, co-existed with restrictive covenants. Unsurprisingly, the most favorable areas for bank investment were also areas where restrictive covenants ensured all-White communities. Although the practice of redlining was made illegal with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the damage had already been done – communities were already established, the seeds of wealth were already planted, and generations of Americans were used to segregated living. As homeownership and wealth data show, the vestiges of these practices are still with us.

Redlining and the Jewish Community

In the 1930s, Portland's bankers and real estate agents systematically discriminated against Catholics and Jews through the practice of "redlining." They defined neighborhoods with a significant "foreign-born, negro, or lower grade population" as "hazardous" and, in so doing, rendered homeowners in those neighborhoods ineligible for mortgages or other property-based loans.

During the same period, Portland's political elites also revised the city's charter to dilute the political power of residents in these neighborhoods. An insurance map, annotated in 1935, draws particular attention to the large number of Irish, Italian, Jewish, and Polish residents in the Bayside, East End, and Munjoy Hill neighborhoods.

Portland was home to over 600 Jewish households in 1930, 87 percent of which had immigrant heads of household. These Jews, however, were more likely to own homes than other Portlanders, an indication of their relative affluence. In part due to the discrimination they experienced downtown, many Jewish families were prompted to move to other neighborhoods, particularly the rapidly growing Woodfords area.

Some wealthy Jews sought to move to high-status towns like Cape Elizabeth, but real estate agents consistently prevented them from doing so. Jews built new synagogues in Woodfords in the 1940s and '50s, abandoning properties in their old neighborhoods like Anshe Sfard.

—David Freidenreich

Pulver Family Associate Professor of Jewish Studies, Colby College

Civil War soldiers assisted formerly enlsaved people to settle in Maine

After the Civil War, as Commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau, General Oliver Otis Howard was responsible for integrating the newly freed Black people into a way of life that was alien and often hostile.

General Howard was also responsible for relocating George Washington Kemp and his family in 1865. Kemp had served with Charles Howard and his older brother, General Oliver Howard after escaping his enslavement in Virginia. Kemp told the story of his journey, saying that he and,

Seventeen other slaves slyly abandoned their master's plantation and enlisted in the army under command of Gen. O.O. Howard. Mr. Kemp, after remaining in service three years, gained the admiration of the General and was persuaded by him to come North to Maine and live, and take care of his farm, on which resided his mother.

General Howard also brought Julia McDermott, a former enslaved person to Maine with her two children at the end of January 1864, when he returned briefly on furlough.

Julia served as cook for Lizzie Howard and her four children in Augusta. At the end of November 1865, Julia married Frederick Brown at the Howard home. Brown, also a former enslaved person, had come to Maine with an officer of the 15th Maine Infantry in 1864.

We can only experience Julia's wedding through the beneficence of Lizzie Howard. I wonder, if Julia were able to tell her own story, on what small particulars of that day would she choose to focus? Would she share her joy at starting her own home with her children and Frederick, her new husband? Would she express feelings of relief, knowing that she, a former slave, could love her husband and children without reservation because there was no danger that they would be ripped apart at a master's whim? To love and be loved is the simplest and most profound of all human emotions, and it is made all the more so by the freedom with which it could now be expressed.

—Krystal Williams

Slavery and Anti-Slavery in Maine

Susannah, an African woman who was about 20 years old when she was brought to Maine in 1686 as an enslaved person, is the first recorded African slave in Maine. Although owning enslaved people was outlawed in Maine in 1783, broader American slavery faced little opposition in Maine until the formation of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. The Anti-Slavery Society's Portland group was integrated with Black and White members, and included both men and women, unusual for the time period.

The Anti-Slavery Society believed slavery was a crime against humanity and a sin against God. Their moral position on abolition alienated those whose livelihoods hinged on the Atlantic slave trade, including merchants, shipping, distilleries, and mills.

Before the Underground Railroad, some abolitionists worked to free enslaved people travelling in the north, by assisting their escape when the enslaved people were visiting places like Maine with their masters.

Reflections on the Last will of Charles Frost of Kittery and Berwick, 1724

One silver-headed loading staff, a plate-hilted sword, and one Negro man (Hector);

One tobacco box, one seal ring, one plate hatband, and one Negro man (Peince);

One riding horse (the best), furniture, pistols, and one Negro man (John); and

All the gold rings (except the seal ring), a steel-hilted sword, and one Negro boy (Cesar).

The riches (and sins) of the father passed to the sons.

Krystal Williams, 2021

Dancing through the race barrier

My name is Garrett Stewart, I am a third-generation Mainer. My grandparents, R. Allen Stewart, Sr. and Mattie Stewart came to Maine during World War II when my grandfather took a job at the South Portland Shipyard. Carrying on the family tradition, I was also a shipfitter at Bath Iron Works. I retired in 2020 due to a work-related injury. I am a member of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW) Local S6 and I am the acting president of the A. Philip Randolph Maine chapter of the Maine AFL-CIO. I also serve on the Permanent Commission for the status on Racial, Indigenous and Tribal Populations in Maine. I feel it is very important to use my voice in today's social climate.

My father, Willie Stewart, was born on November 22, 1945, in Portland. He graduated from high school in 1964 and was considered one of the best athletes to attend Deering High School. In addition to football and track he was also a professional boxer with a 9-1 record fighting at the Portland Expo. My father was a hard worker and for most of his early life worked for my grandfather at Stewart Paving Company.

During the 1960s when he was a teenager, my father was a weekly guest dancing with White teens on the Dave Astor show—Maine's version of American Bandstand that was broadcast throughout the state on Saturday nights. Although this was a common sight for people in this area, Jim Crow was still segregating the South. I don't believe my father truly knew what a big deal that was at the time. He had been here all his life and had wonderful lifelong friends of all backgrounds.

—Garrett Stewart

Portland, Maine

My family and Malaga Island

When I look at the photos of my family on Malaga Island I have mixed emotions. In one way it's exciting because these images provide a connection to my grandfather and extended family that I hadn't had. It helps connect the dots of who we are. I love seeing the cozy home and relationships. I imagine what they did for fun and the ways that joy showed up in their lives. I wonder who in our family has what traits passed down and wonder what they'd think of us after all that has happened.

In other ways it's saddening, I only met my grandfather once as a child and had heard that he was troubled. I feel like what we now know about his life offers some insight into why he may have been that way. So much trauma and loss. Processing that could not have been easy. Feeling displaced and disregarded had to be infuriating.

I can't help but focus on their eyes in the images. I wonder what they felt in these moments. If they wanted to take the photo. If the person on the other end of the camera was a friend or foe. I wonder about their concerns, fears, and agency. I wonder how they found so much strength after being deemed worthless.

In other ways, the images are motivating. The Tripp family are the only remaining descendants of Malaga Island residents who identify as Black/African American. Despite the treatment, the Tripps are still here. We are thriving and living in ways that they may have only imagined. I look at these images and feel pride and am honored to carry on their legacy.

—Charmagne Tripp

Grammy Award-winning singer and songwriter

Indentured Servitude as a model for child labor and inequity

Societies have always grappled with how to support their poorest members, and Maine is no exception. In 1821, the year after Maine became a state, the legislature passed a law providing for the "Relief and Support, Employment and Removal of the Poor." Residents were assigned to towns, who were charged with supporting the poor and indigent through the work of special boards, the "Overseers of the Poor." At taxpayer expense towns created poor farms and tenements to house the poor, where they could work in exchange for food and shelter. This indentured servitude created classism based on inequity that opposed the Framer's sentiments that "all men are created equal."

Not surprisingly, towns sought ways to minimize their costs, and one of the most expedient strategies was a system known as "vendue," in which the poor were auctioned off to the lowest bidder, the town then paying the winning bidder for the care provided. These auctions often took place in a public venue such as the town square, in ways reminiscent of a slave auction.

When families fell on hard times the Overseers could bind out their children into apprenticeships with local farms and businesses. Boys could be indentured until they reached the age of 21, and girls until they turned 18 or were married, whichever came first. Masters receiving these children were supposed to feed, clothe, and educate them, in addition to teaching them a trade that would allow them to support themselves after their indentureship. Child labor through servitude served as a model for children's work in factories and mills.

Equal Rights Amendment of 1972

In 1923 the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was first introduced into Congress. Drafted by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman, it came soon after women won the right to vote through the 19th Amendment. Paul always understood that the vote would not solve all of women's problems. "We shall not be safe until the principle of equal rights is written into the framework of our government," she said.

Yet most women's organizations opposed the ERA over the worry it would be used to strike down laws protecting working women. Many believed the shorter workdays, minimum wage laws, age of consent and other protections women had fought so hard for were at risk. They argued that America wasn't ready. There were too few women in positions of power—such as legislators, lawyers, judges, employers and union leaders—to make good on the promises of the ERA.

Congress finally passed the ERA in 1972. Supporters were given seven years to get it ratified, later receiving a three-year extension. But by 1982, they were still three states short.

In the last few years, the three final states ratified the ERA; Nevada (2017), Illinois (2018), and Virginia (2020). Congress must decide whether to eliminate the original deadlines.

Section 1 of the ERA reads: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." In 2021 it is astounding that, under our nation's—and our state's—founding documents, women are still not considered equal.

—Anne Gass

Voting, Suffrage and the Electoral College

Who is a citizen? Who can vote? These issues have been debated throughout our nation's history. The U.S. Constitution's framers recognized the importance of voting rights, who decided them, and how elections were conducted. This resulted in the system still in place today, where states generally manage elections, but Congress can also pass voting laws or regulations.

The Constitution first granted citizenship and voting rights only to White men who owned property—such as land or slaves—but eventually the property ownership requirement was dropped. This gave White men the power to fashion a system of laws that privileged their interests above those of others.

Extending the vote to groups other than White men would prove far more difficult. It took the Civil War to enfranchise Black men, through the combined power of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. It was another half-century of struggle until, in 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified through which most—though not all—women won the right to vote.

Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, which finally recognized Native Americans as citizens, but they couldn't vote until 1962. In Maine, Native Americans weren't allowed to vote in state elections until 1967.

Today, the tug of war over voting rights continues. The U.S. Supreme Court's 2013 decision for Shelby County vs. Holder eviscerated many of the protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the 2020 election, states loosened voting restrictions to keep people safe during a dangerous pandemic, but in 2021 many states are seeking to roll those back and take further steps to restrict voting access.

There is also serious debate over eliminating the electoral college and instead using the national popular vote to elect the U.S. President. The electoral college was a compromise by the Constitution's Framers. Further, it gave Southern states an outsize share of power by allowing them to count three-fifths of their slaves in apportioning votes (even as they were denied voting rights). The system has been criticized because it is currently possible for candidates to win the popular vote, but lose the electoral college, as happened in 2000 and 2016.

Clearly, we are still striving to achieve the "more perfect union" envisioned by the preamble to the United States Constitution, that "secures the Blessings of Liberty" to all Americans.

—Anne Gass

We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor

Dehumanization and violence

How do you identify yourself? Probably by a myriad of roles based in your family, race, language, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and the expectations that society puts upon you.

Some roles are easily accepted, cemented into the infrastructure of the United States—first through the Doctrines of Christian Discovery and Domination and later to the U.S. government's preference toward wealthy, straight, White men. Some identities, emboldened by society—religion, kin groups or clans, class, governments, and laws—use varying levels of force to control people. Over the past 500 years in what is now known as Maine, stereotypes and laws have created a system of lasting discrimination and intolerance, often seen as harmless until it explodes into mob violence.

Wabanaki people have been dehumanized as "savages," victims of state-sanctioned genocide, their children have been stolen and adopted into White homes to force assimilation, and there is a continuing epidemic of violence against Indigenous women.

Catholics and other non-Protestant faiths along with immigrants and Black people have faced slurs, been expelled from towns, and were tarred and feathered to enforce compliance—often at the hands of hate groups like the "Know Nothings," the predecessors of the Ku Klux Klan.

Patriarchal laws, discrimination, and sexism have impeded the ability of women, gender non-conforming, and LGBTQ2+ people to fully participate in society; those who stepped out of line often saw brutal consequences.

Corsets, Rosie the Riveter, and Leave it to Beaver

For centuries, women have worn corsets, or laced bodices, to embody society's perceptions of beauty relating to the female figure. Corsets fulfill a desire for a tiny waist and full bust. Over time, the tight lacing can cause physical deformities, and women from the 15th to 19th centuries damaged their health from the constriction. Corsets were tied tightly with as many as fifty laces, supposably to impose modesty upon the wearer—even children.

Corsets began as a marker of class and society. Later they were seen as a form of female oppression and victimization. Today they are sometimes used as a symbol of empowerment and feminine rebellion a-la the pop star Madonna in the 1980s.

During World War II, with men fighting on the frontlines of the war, factories, military units, and other male-dominated industries were desperate for labor. Advertising propaganda— think Rosie the Riveter—encouraged women to leave their homes and join the World War II effort.

After the war, the same propaganda machines worked to force women back into domestic roles. "Leave it to Beaver" stereotypes of the nuclear family enforced gender roles which bolstered consumerism and traditionalism among the American public after World War II.

Margaret Chase Smith goes to Washington

Women's path to politics often led through their husbands. The convention of the "widow's mandate" became popular after women won the vote in 1920, and involved appointing or advancing by special election a woman to fill out the congressional term of a husband or other male relative.

When Margaret Chase Smith's husband died in 1940, she replaced him in the U.S. House of Representatives and went on to serve eight years in the House before being elected to the U.S. Senate—the first woman elected to the Senate in her own right and the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress.

Margaret Chase Smith Presidential Campaign Hat, 1964

Item Contributed by

Margaret Chase Smith Library

Smith was a Republican but she had a strong independent streak. She is perhaps best known for her Declaration of Conscience speech in 1950, in which she denounced the tactics used by her colleague Joseph McCarthy in his anti-communist crusade. "I don't like the way the Senate has been made a rendezvous for vilification, for selfish political gain at the sacrifice of individual reputations and national unity," she said. Smith herself had been smeared as a Communist during her earlier campaigns, which may have led to her opposition to McCarthy.

Often the only woman in the Senate, Smith chose not to limit herself to "women's issues," making her mark in foreign policy and military affairs. She established a reputation as a tough legislator on the Senate Armed Services Committee. She also co-sponsored the Equal Rights Amendment and supported civil rights, Medicare, and increased funding for education. She ran for president in 1964.

Smith was known for her signature hats and pearls. While Smith noted the discrimination she faced as a woman, her campaign song, Leave it to the Girls by Gladys Shelley, embraced gender stereotypes:

But leave it to the girls

They're heaven sent

It could be that our next president

Will wear perfume and pearls

Be diplomatic in pin curls

For love and glory leave it to the girls!

Women's Resistance

On January 21, 2017, people walked peacefully in solidarity with the Women's March in Washington DC in support of human rights, women's rights, and justice. An estimated 10,000 people in Augusta and 15,000 in Portland marched. Maine Historical Society collected signs, buttons and objects from the events.

Ellen Crocker of Bethel was 78 when she attended the Women's March in Augusta. She said, "I was at a loss as to what an old lady could do. I went on Etsy and found someone who would make me a batch of my design." Her Purr-Sist buttons are a tip to Elizabeth Warren, pussy hats, and sisterhood.

The equal freedom to marry

Why did it take a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court for same-sex couples to be able to marry nationwide? After all, deciding whether and whom to marry is an intensely personal decision and is associated with a life partnership of love, commitment, mutual responsibility and care. Our society allows individuals, not the government, to make that choice for themselves.