Keywords: Manufacturing industries

Item 27815

Garland Manufacturing Co., Saco, ca. 1965

Contributed by: Dyer Library/Saco Museum Date: circa 1965 Location: Saco Media: Photographic print

Item 14659

Accident report, Eastern Manufacturing Co., Brewer, 1927

Contributed by: City of Brewer Date: 1927-02-19 Location: Brewer Media: Ink on paper

Item 110109

Cook, Everett & Pennell office space, ca. 1923

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: circa 1923 Client: Cook, Everett & Pennell Architect: John P. Thomas

Item 111799

Cook, Everett, & Pennell building alterations, Portland, 1945-1946

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1945–1946 Location: Portland; Portland Client: Cook, Everett, & Pennell Architect: John Howard Stevens and John Calvin Stevens II Architects

Exhibit

Silk Manufacturing in Westbrook

Cultivation of silkworms and manufacture of silk thread was touted as a new agricultural boon for Maine in the early 19th century. However, only small-scale silk production followed. In 1874, the Haskell Silk Co. of Westbrook changed that, importing raw silk, and producing silk machine twist threat, then fabrics, until its demise in 1930.

Exhibit

Biddeford, Saco and the Textile Industry

The largest textile factory in the country reached seven stories up on the banks of the Saco River in 1825, ushering in more than a century of making cloth in Biddeford and Saco. Along with the industry came larger populations and commercial, retail, social, and cultural growth.

Site Page

Historic Hallowell - Early Industry and Bombahook

"Early Industry and Bombahook Industry develops quickest where raw materials meet easy transportation and ready energy, both human and otherwise."

Site Page

Historic Hallowell - Industry and Immigrants-A Changing Community

"… the waterfall” – between maritime commerce and manufacturing – was over. The Cotton Mill, built in 1844 as the Hallowell Cotton Factory, initially…"

Story

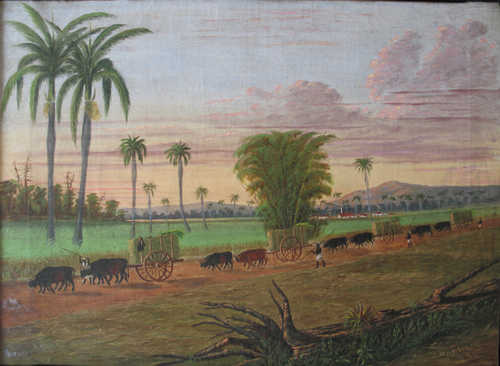

Maine and the Atlantic World Slave Economy

by Seth Goldstein

How Maine's historic industries are tied to slavery

Story

My 40 years in Forestry and the Paper Industry in Maine

by Donna Cassese

I was the first female forester hired by Scott Paper and continue to find new uses for wood.

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: English Language Arts, Social Studies

Most if not all of us have or will need to work in the American marketplace for at least six decades of our lives. There's a saying that I remember a superintendent telling a group of graduating high-school seniors: remember, when you are on your deathbed, you will not be saying that you wish you had spent more time "at the office." But Americans do spend a lot more time working each year than nearly any other people on the planet. By the end of our careers, many of us will have spent more time with our co-workers than with our families.

Already in the 21st century, much has been written about the "Wal-Martization" of the American workplace, about how, despite rocketing profits, corporations such as Wal-Mart overwork and underpay their employees, how workers' wages have remained stagnant since the 1970s, while the costs of college education and health insurance have risen out of reach for many citizens. It's become a cliché to say that the gap between the "haves" and the "have nots" is widening to an alarming degree. In his book Wealth and Democracy, Kevin Phillips says we are dangerously close to becoming a plutocracy in which one dollar equals one vote.

Such clashes between employers and employees, and between our rhetoric of equality of opportunity and the reality of our working lives, are not new in America. With the onset of the industrial revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, many workers were displaced from their traditional means of employment, as the country shifted from a farm-based, agrarian economy toward an urban, manufacturing-centered one. In cities such as New York, groups of "workingmen" (early manifestations of unions) protested, sometimes violently, unsatisfactory labor conditions. Labor unions remain a controversial political presence in America today.

Longfellow and Whitman both wrote with sympathy about the American worker, although their respective portraits are strikingly different, and worth juxtaposing. Longfellow's poem "The Village Blacksmith" is one of his most famous and beloved visions: in this poem, one blacksmith epitomizes characteristics and values which many of Longfellow's readers, then and now, revere as "American" traits. Whitman's canto (a section of a long poem) 15 from "Song of Myself," however, presents many different "identities" of the American worker, representing the entire social spectrum, from the crew of a fish smack to the president (I must add that Whitman's entire "Song of Myself" is actually 52 cantos in length).

I do not pretend to offer these single texts as all-encompassing of the respective poets' ideas about workers, but these poems offer a starting place for comparison and contrast. We know that Longfellow was the most popular American poet of the nineteenth century, just as we know that Whitman came to be one of the most controversial. Read more widely in the work of both poets and decide for yourselves which poet speaks to you more meaningfully and why.