Keywords: Native American names

Item 6242

Pere Pole deposition, Hallowell, 1793

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1793-07-19 Location: Hallowell Media: Ink on paper

Item 1042

Mustering Spanish-American War, 1898

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1898 Location: Augusta Media: Photographic print

Item 111491

Isaacson residence floor plan and presentation drawing, Lewiston, 1960

Contributed by: Maine Historical Society Date: 1960 Location: Lewiston Client: Philip Isaacson Architect: F. Frederick Bruck; F. Frederick Bruck, Architect

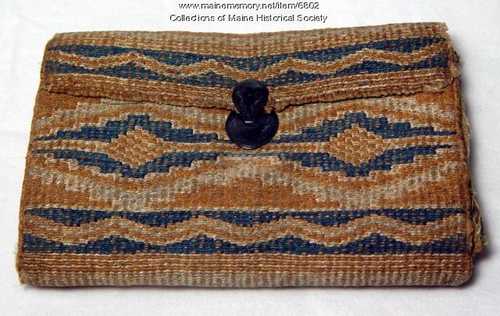

Exhibit

Gifts From Gluskabe: Maine Indian Artforms

According to legend, the Great Spirit created Gluskabe, who shaped the world of the Native People of Maine, and taught them how to use and respect the land and the resources around them. This exhibit celebrates the gifts of Gluskabe with Maine Indian art works from the early nineteenth to mid twentieth centuries.

Exhibit

2009 marked the bicentennials of the births of Abraham Lincoln and his first vice president, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. To observe the anniversary, Paris Hill, where Hamlin was born and raised, honored the native statesman and recalled both his early life in the community and the mark he made on Maine and the nation.

Site Page

Presque Isle: The Star City - Native Americans

"… Native Americans The Deep History of Presque Isle Text by: David Putnam In 1978, as a result of the proposal to construct the Aroostook Centre…"

Site Page

Music in Maine - Community Music

"… and Music Alive By Cindy Larock A “Franco-Yankee” native of Lewiston, I've been happily involved in the traditional music and dance scene in Maine…"

Story

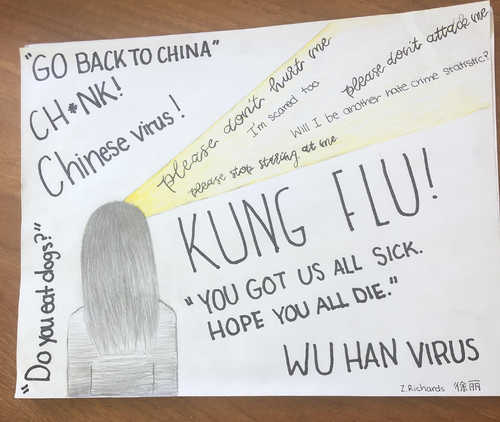

An Asian American Account

by Zabrina

An account from a Chinese American teen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Story

Mali Agat (Molly Ockett) the famous Wabanaki "Doctress"

by Maine Historical Society

Pigwacket Molly Ockett, healing, and cultural ecological knowledge

Lesson Plan

Grade Level: 9-12

Content Area: Social Studies, Visual & Performing Arts

When European settlers began coming to the wilderness of North America, they did not have a vision that included changing their lifestyle. The plan was to set up self-contained communities where their version of European life could be lived. In the introduction to The Crucible, Arthur Miller even goes as far as saying that the Puritans believed the American forest to be the last stronghold of Satan on this Earth. When Roger Chillingworth shows up in The Scarlet Letter's second chapter, he is welcomed away from life with "the heathen folk" and into "a land where iniquity is searched out, and punished in the sight of rulers and people." In fact, as history's proven, they believed that the continent could be changed to accommodate their interests. Whether their plans were enacted in the name of God, the King, or commerce and economics, the changes always included and still do to this day - the taming of the geographic, human, and animal environments that were here beforehand.

It seems that this has always been an issue that polarizes people. Some believe that the landscape should be left intact as much as possible while others believe that the world will inevitably move on in the name of progress for the benefit of mankind. In F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby a book which many feel is one of the best portrayals of our American reality - the narrator, Nick Carraway, looks upon this progress with cynicism when he ends his narrative by pondering the transformation of "the fresh green breast of a new world" that the initial settlers found on the shores of the continent into a modern society that unsettlingly reminds him of something out of a "night scene by El Greco."

Philosophically, the notions of progress, civilization, and scientific advancement are not only entirely subjective, but also rest upon the belief that things are not acceptable as they are. Europeans came here hoping for a better life, and it doesn't seem like we've stopped looking. Again, to quote Fitzgerald, it's the elusive green light and the "orgiastic future" that we've always hoped to find. Our problem has always been our stoic belief system. We cannot seem to find peace in the world either as we've found it or as someone else may have envisioned it. As an example, in Miller's The Crucible, his Judge Danforth says that: "You're either for this court or against this court." He will not allow for alternative perspectives. George W. Bush, in 2002, said that: "You're either for us or against us. There is no middle ground in the war on terror." The frontier -- be it a wilderness of physical, religious, or political nature -- has always frightened Americans.

As it's portrayed in the following bits of literature and artwork, the frontier is a doomed place waiting for white, cultured, Europeans to "fix" it. Anything outside of their society is not just different, but unacceptable. The lesson plan included will introduce a few examples of 19th century portrayal of the American forest as a wilderness that people feel needs to be hesitantly looked upon. Fortunately, though, the forest seems to turn no one away. Nature likes all of its creatures, whether or not the favor is returned.

While I am not providing actual activities and daily plans, the following information can serve as a rather detailed explanation of things which can combine in any fashion you'd like as a group of lessons.

Lesson Plan

Wabanaki Studies: Stewarding Natural Resources

Grade Level: 3-5

Content Area: Science & Engineering, Social Studies

This lesson plan will introduce elementary-grade students to the concepts and importance of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Indigenous Knowledge (IK), taught and understood through oral history to generations of Wabanaki people. Students will engage in discussions about how humans can be stewards of the local ecosystem, and how non-Native Maine citizens can listen to, learn from, and amplify the voices of Wabanaki neighbors to assist in the future of a sustainable environment. Students will learn about Wabanaki artists, teachers, and leaders from the past and present to help contextualize the concepts and ideas in this lesson, and learn about how Wabanaki youth are carrying tradition forward into the future.