James Leamon

Item 17247 info

Maine Historical Society

Professor James Leamon explores the significance of a series of letters from William Bayley, a Revolutionary War soldier, to his mother in Falmouth (Portland).

Leamon, professor emeritus of Early American History at Bates College, is the author of The Revolution Downeast: The War for American Independence in Maine (The University of Massachusetts, 1993). He also is co-editor of Maine in the Early Republic (The University of New England Press, 1988) and a contributor to Maine: The Pine Tree State (The University of Maine Press, 1995).

Click on the play button to hear Professor's Leamon's introduction to this collection of documents:

Transcription of Leamon's comments:

The sixteen documents in the William Bayley collection offer insights into the military career of William Bayley of Falmouth, now Portland, Maine, a common soldier who served in the American army during most of the Revolution. Letters from William to his mother back home in Falmouth constitute the bulk of the collection, which includes only one from the many that Mrs. Jean Bayley wrote to her solider son. Nonetheless, these documents are as revealing of life on the home front as they are of life in the military, and collectively reveal much about the impact of the war on family relationships.

William Bayley to mother, October 15, 1777

Item 10548 info

Maine Historical Society

William Bayley, a soldier in the Continental Army, wrote to his mother, Jean Bayley of Falmouth, from New City on October 15, 1777.

Click on the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments about this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

William Bayley's letters home are invariably brief and matter-of-fact. He writes about his health, which was astonishingly robust, life in the military, such as the lack of pay and clothing, and why he cannot come home as his mother requests repeatedly.

His combat experiences included Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga in 1777, the infamous winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, and the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey, 1778. But details and emotions are rare; seldom does Bayley step out of his role as reporter of events except, for example, after Burgoyne's surrender when he writes jubilantly, "Our people since I wrote the first of this letter have taken Burgoyne's Army with all their artillery and baggage and have sent down into the country bearing six or seven thousand besides Tories. This is greatest exploit the Americans have done yet."

Washington at Valley Forge, 1777

Item 17522 info

Maine Historical Society

William Bayley was one of the soldiers at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, during the winter of 1777-1778 when George Washington chose it as his winter quarters.

Bayley wrote to his mother from the encampment there.

The poorly outfitted troops suffered from the cold and lack of supplies.

Letter from William Bayley to mother, October 23, 1780

Item 10555 info

Maine Historical Society

Bayley in October 1780 tried to allay his mother's fears by telling her he had not reenlisted as she had heard and that he would be home in two months.

Click on the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments on this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

Another recurring theme throughout Bayley's letters to his mother is the poverty experienced by the typical American soldier, especially the lack of pay and of clothing. Bayley's letters make it clear how dependent soldiers were on family and hometowns for necessities such as shoes, stockings, and mittens, and so forth. But he does not whine or complain, he merely states his needs in unemotional terms: having described and exulted over Burgoyne's defeat, Bayley states laconically, "I should be glad if you could you send me a pair of mittens and some needles and thread and I will send you some money as soon as I get my wages. I have not had but four months wages since I come but I expect to have some soon."

William Bayley to mother, October 30, 1778

Item 10552 info

Maine Historical Society

William Bayley wrote to his mother from Hartford on October 30, 1778, suggesting she go to the local (Falmouth) committee to get reimbursed for items she sent him.

Click on the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments on this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

In a different letter to his mother from Hartford, Connecticut, Bayley hears things are very expensive at home and hopes she will be provided by the blessing of God "and that he has sent her five dollars which is all he can do at present " and he urges her to get compensation from Falmouth's town committee for the shoes and stockings she has sent to him, but which Bayley apparently never received.

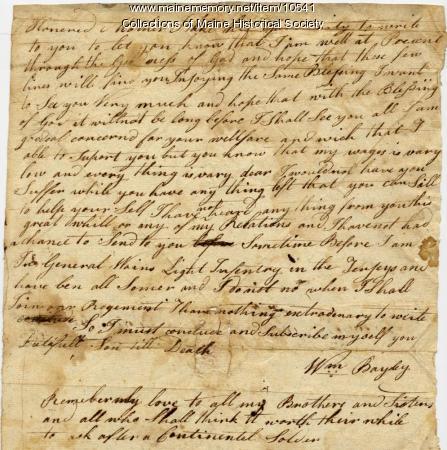

William Bayley letter to mother, Jean Bayley, from Continental Army, ca. 1778

Item 10541 info

Maine Historical Society

In an undated letter, Bayley expressed regret that he could not support his widowed mother because his wages were so low.

Click the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments about this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

As many of his letters home imply, conditions at home were almost as difficult as for men in the service. In an undated letter, probably 1778, Bayley writes to his widowed mother he is sorry to hear of hard times at home, but says he has no money to help her, so urges her to sell what she can to survive.

George Washington at Monmouth, 1778

Item 17524 info

Maine Historical Society

Among the battles in which Bayley fought was Monmouth Court House in New Jersey, where George Washington took command of American troops in June 1778 after American Gen. Charles Lee ordered a retreat.

This was the last major battle in the northern colonies during the Revolutionary War.

William Bayley to mother, May 9, 1779

Item 10553 info

Maine Historical Society

Bayley tells his mother that he is staying in a private home near Philipsborough and is not sure when he would join his regiment again. He expresses concern for her financial condition.

Click on the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments on this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

One year later from Philipsborough, New York, Bayley again sympathizes over his mother's hardships, expressing his inability to help, and urges her to put her trust in God. He writes, "You likewise informed that it was hard times with you which I am very sorry to hear and am very sorry that I am not able to help you but I cannot at present. I take it that you put your trust in God who is the husband of the widow and the Father of the fatherless and is able to provide for all who trust in him."

Jean Bayley letter to son, July 12, 1781

Item 10556 info

Maine Historical Society

Jean Bayley writes to William to find out why she has not heard from him and why he has not returned to Falmouth before the winter of 1780-81.

Click on the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments on this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

Conditions at home got no better for Widow Bayley, in 1781 she writes to her son from Falmouth in the most piteous terms, "I would inform you that the farm lays common as all my sons is gone away. I should be glad if you would come home or write to me the reason of your not coming so that I may know what to depend upon. So I remain your loving mother till death shall part. Jean Bayley"

British surrender to George Washington, 1781

Item 17487 info

Maine Historical Society

When the British surrender came, William Bayley was in West Point, where he remained.

The engraving depicts the British surrender at Yorktown that ended the Revolutionary War. American Commander George Washington accepts the surrender.

The title is "The British surrendering their Arms to Gen. Washington after their defeat at York Town in Virginia October 1781."

William Bayley letter to mother, October 7, 1781

Item 10557 info

Maine Historical Society

Bayley in October 1781 told his mother he could not come home because he was awaiting back pay that he would lose if he left the West Point area.

Click on the play button to hear a recording of Professor Leamon's comments on this letter:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

Judging from this collection of letters, William Bayley never did come home, at least as the typical 'dutiful young son' to redeem the family farm and provide comfort to this mother in her declining years. This would have been his traditional familial role, probably then he would have inherited the family farm.

But despite his mother's repeated urgings, and his own frequently expressed desires and promises to do so, soldier Bayley never found the right occasion. Most of the time military necessity prevented his return, but other times his own lack of money and proper clothes stood in the way. In 1781 when his own enlistment was over, he even re-enlisted as a three-months volunteer to take the place of one of the regular recruits for that length of time.

Letter from William Bayley to mother, September 11, 1782

Item 10558 info

Maine Historical Society

After an absence of some four years, Bayley writes to his mother, Jean Bayley of Falmouth, a widow, that he had married Sarah Linch a month previous and expected to visit Falmouth in the winter.

Click on the play button to hear Professor Leamon's comments:

Transcription of Professor Leamon's comments:

In short, William Bayley's military experience in the Revolution had gradually severed his ties to family and to Falmouth, Maine. The last letter of the collection, dated 1782 from West Point, reveals the final step in the process. Note the stiff formality of the salutation (Dear Madam) as opposed to the usual 'Honored Mother' even 'Dear Mother' in one letter, and the startling revelation that he is married without his mother's approval. "Dear Mother I hope you will not take it hard but excuse me when I tell you of my marriage. I could have wished for your advice and approbation but the distance between us would not admit of it. Tis needless for me to say much of the reason or of her character. If I had not have liked her I should not have had her. However I think her deserving of as good as I am."

A second startling comment is when Bayley writes, "She was bred at a place called Smith's Clove where I now make my home although I work at West Point. Tis hardly a month since our marriage. I do expect to see you next winter if I am well. Let the consequences be what will." The important point is that Bayley's home is no longer Falmouth, Maine. And while he promises to return to Falmouth to visit his mother, it will only be as a visitor, who intends to return to his new home and new wife.

This letter is William Bayley's declaration of independence from the traditional ties that bound him to Falmouth and to his family there. Now a new life with a new wife in a new location - upper state New York - beckons. Thus was the Revolution as radical an experience for William Bayley as it was for the thirteen colonies that broke their traditional ties to their mother country.

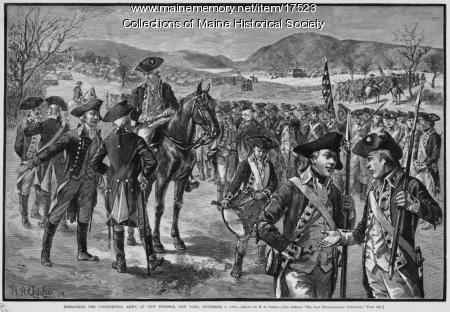

Disbanding the Continental Army, November 3, 1783

Item 17523 info

Maine Historical Society

By the time the Continental Army was disbanded, William Bayley was married and living in New York. He apparently never returned to Portland to live and little is known about his life after his marriage.

A drawing by H. A. Ogden depicts the disbanding of the Continental Army at the end of the Revolutionary War, November 3, 1783, in New Windsor, New York. The drawing was published in Harper's Weekly on October 20, 1883, page 664.

This slideshow contains 13 items